Wrought iron

"Wrought iron" is the generally used term for soft, non-homogeneous iron which was produced throughout the world by traditional blast-furnace smelting techniques before the invention of the homogenizing Bessemer process in the 1850s. Until then, it was the most common material used for all plastic-formed hardware and iron objects, architectural and otherwise. Its small silica content gives it a visible grain under heat and oxidation, which reveals beautifully when polished and etched. It generally welds easily to itself and other steels, but must be worked at a high temperature to prevent splitting along its grain lines. It contains very little carbon, making it soft and malleable but unsuitable for tool or blade edges since the lack of carbon makes it unhardenable. Traditionally, it was used for tool bodies which had higher-carbon alloys forge-welded to its working surfaces (i.e., a steel face welded to a wrought iron hammer body, a steel edge on a wrought chisel, or a steel edge on a wrought knife). It differs greatly from cast iron, which has such a high carbon content that its melting temperature is lowered greatly but is then so brittle that it cannot be forged or welded. It is easily and commonly found anywhere with a history of human settlement, if you know where to look.

Shear steel

A less common term than "wrought iron", shear steel (or blister steel) is part of the smith's lexicon for wrought iron whose carbon content has been raised by baking it at temperature for some time among an agent like charcoal or bone, whose carbon migrates into the molecular matrix of the iron, transforming it into the solid mixture we call "steel". It retains its grainy pattern and silicate inclusions, but gains the ability to be hardened by quenching once it has reached a temperature where its crystal matrix reaches a martensitic cubic structure. Again, this type of steel is non-homogeneous and generally pre-dates the Bessemer process. It can be found in old tools and objects that needed wear- or tensile strength, such as springs.

Bloom steel / hearth steel

Possibly the most eccentric to define, bloom- and hearth steel are metallurgically indistinguishable in many regards but differ in the process by which they are made. Both are produced in a home-made furnace historically constructed with a clay stack and some kind of tuyere, which is a pipe through which air is forced into the bottom of the furnace. Charcoal is burned in the furnace and continually fueled until a certain temperature and reducing atmosphere is achieved within it. To make bloom steel, which is the oldest human-made steel, iron ore (naturally-occurring iron oxide) is added to the furnace along with the charcoal where it lets go of its oxygen and "reduces" into a spongy mass of iron, called a "bloom". The porous bloom is pulled from the furnace and compacted by forging into a bar of iron which can then be further refined by drawing out and folding. Hearth steel differs in that it is not directly reduced for ore, but rather steel or iron scraps are fed into the furnace, where they melt and re-coagulate into a bloom as well, which is then processed the same way. Both processes can create highly diverse steels, which are always different and quite non-homogeneous.

Historically, bloom irons and steels are made according to the most ancient human techniques of ironworking, based on archaeological evidence and its continuous living practice in west African societies. Hearth-melting is probably equally old and served to recycle small, unusable scraps of valuable metal or to either raise or lower the carbon content of stock, if what was needed was scarce. The revival of these methods among smiths today allow modern craftspeople to physically experience the ancient smith's manual relationship with the material they worked.

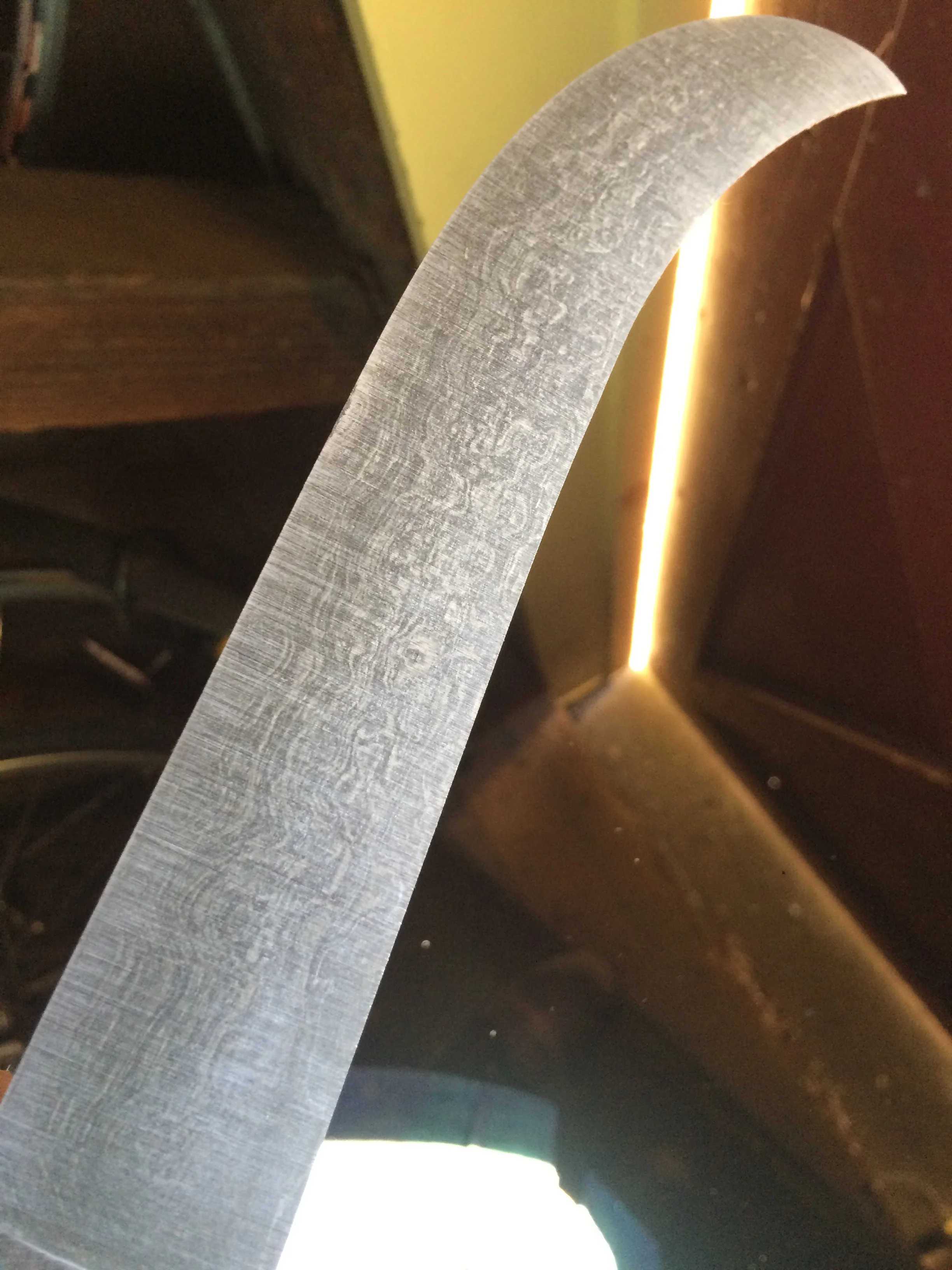

Pattern-welded steel

Pattern-welding is a process by which steels of different compositions are intentionally layered or laminated to form visible patterns. This is most common in blades, and was commonplace among skilled bladesmiths in many parts of Europe, the Middle East, and Asia during the Iron Age and later. Though the techniques of layering and forge-welding were the same as the making of laminated tools with iron bodies and steel edges, pattern-welding pushed this utilitarian method into an aesthetic realm, where the different carbon contents of steels assigned them contrasting visual identities that could be mixed and molded to a smith's composition. Arguably the most impressive historical examples of this technique are the swords and saxes made in Northern Europe and Scandinavia throughout the 1st century AD.

Today's bladesmiths have wildly exploited pattern-welding with modern alloys and machinery, pushing the medium to make frankly unbelievable patterns that share very little with the traditional aesthetics of the technique. However, the basic technical premise is the same, and no doubt smiths of all eras were the most daring and original they could have been with the means available to them.